A SPECIAL LECTURE ON AERONAUTICS (WHERE THERE IS NO RUNNING WATER)

The village of Chona, Zambia is not really a village at all but more of a focal point, a place of infrastructure where the wider community gathers. It has a health clinic, a school, a small market and a water well, meaning every day the community for miles around descend to Chona before heading back to their small plots of land and mud huts in the evening. It is here at the local school, with so many pupils that the school starts at 7am to 5pm working in two shifts, where I offered to give a lecture on Aeronautics to the eldest math and physics class.

There aren’t many places in Africa that resemble the stereotypical view that permeates in Europe, but Chona can be described as one of them. The ground is a reservoir of orange-brown dust that diffuses into the air under the slightest disturbance. The roads being a slightly harder packed dirt, intersect the plots of land of looser dirt. A wiry, beige and hardy grass clings onto little pockets of dirt well away from human feet. Shrubs with deeper roots stand with more pride but with an equally hardened exterior to the extreme heat they have to cope with. Standing highest of all are the few trees that grow intermittently across the village, their roots penetrating deep into the ground, into the water table below. The trees are treasured, their branches and leaves offering some of the only shade available for the heat-stricken inhabitants. Without shade the heat is debilitating: The midday sun screeches at the skin with a silent stare, proud and unrelenting, all activity stops under her command. The inhabitants disappear to find some respite – no one is out in the open, they learnt that long ago. The shade offered by the tree is taken, the sides of the few buildings are taken and the shrubbery is all that is left for the ill prepared.

The people of Chona are part of the Nyanga tribe, their skin a smooth deep brown-black. Their faces are open and friendly with large white teeth that smile often. Every encounter happens with a shake of the hand, a greeting and questions about your health. There is a light and unbounding happiness that radiates their eyes which can turn to concern and back to humour in a blink of an eye depending on the turn of the conversation. As is typical in almost all cultures, the women dress traditionally, garments of loose fabric, beautifully coloured and the men in western clothing – shirt and trousers and leather shoes for the proud men, t-shirt and jeans for the youth. Visitors are kings here and are treated with reverence.

We were here visiting a Japanese nurse, Momo, that we had met in the capital a few days earlier. Her home was a small two room bungalow, one of the few brick buildings of the village. The toilet was an outhouse a few metres behind the house with a deep pit that would serve for a year or so before it had to be moved. There was always a constant of activity around us; the villagers came to use the tap for the well that was situated just next to our tent. They came and filled up their buckets for the day and night. The pump only operated for 3-4 hours a day depending on electricity and that supplied water for the whole village and beyond.

Most people lived outside of Chona, in small clusters of mud huts with thatched roofs in clearings surrounded by fields. Cotton is the only crop we saw growing, a cash crop and one to sell, not to consume. They take great pride in their houses and clearings, sweeping the dusty ground outside for any rubbish and debris leaving an immaculate and brown scene. The mud huts offer an amazing amount of insulation against the heat and remain cool throughout the day. They cook using a small rudimentary barbeque style stove, filled with coal. A small hot coal is all that it would take to light the stove and carefully placed inside the stack the stove is swung in a pendulum motion until the movement of fresh air makes the whole stove start smoking. Calls punctuate the silence of the setting sun, ‘Momo, do you have a light?’ ‘Yes, come’ she responds and the visitor, typically a young girl, walks over carrying their stove with them. A hot coal would be transferred to the visitors and she would start swinging in a practiced and expert arc until the whole stove is alight. They come to Momo because she’s one of the few people that can afford matches and some kerosene and so her stove is always burning first.

Momo worked in the health clinic that was 100 metres from her house during the day, helping out the other nurses, treating the ailments of inhabitants of Chona and the surrounding villages; it is the only health clinic for miles around. The clinic is a series of single story buildings covering a plot of dusty ground on the edge of the village and moments from the nurses’ houses. The buildings are fairly new, with a fresh coat of white paint on their walls. The bottoms of the buildings are stained with the umber dust that coats everything it comes into contact with. For the number of patients seeking medical help it is vastly understaffed. The patients walk for hours and sometimes days to see a doctor, but often the queue is too long and many are turned away each evening when the clinic closes.

Our stay in Chona was centred around the clinic. The nurses were excited to have visitors and were proud to show us their work. But seeing this clinic and the strain it was under trying to cope with the quietly suffering queue of patients we wanted to do more. Momo told us of the current bottleneck in the registration room, which was more like a closet that the patients had to attend before joining the queue for the doctor. All patients, at least ones that had already attended the clinic once before, had a registration booklet which was just an exercise book. The books are kept in the registration closet for fear that the patients would lose them if they took them away with them. They queue outside waiting for someone to open up and start finding their books but the nurses are busy, the doctor is busy and often there is no one to register the patients. Only when there are some helpers around that this task is fulfilled. For the days that we were there, we took over this task.

The closet is a mess of books, half organised by year or registration number, in piles of hundreds on broken shelves that stretches from the floor to the ceilings. The books occupy the shelves and the floor next to the shelves and on the floor behind the door. They’re organised by a registration number which are given to the patients on a torn up piece of card from a medicine box. Most patients remember to bring this piece of card with them and finding the right book is made simple. Meanwhile the queue gets longer and longer, patiently waiting as we rifle through piles of dusty books, beads of sweat running down our heads in this oven of a room.

By 11am the temperature is too hot and there are no new patients. Instead the bottleneck is at the doctor’s surgery and the patients wait quietly and patiently in the concrete waiting area. Thankfully there is a roof keeping the sun off them. The doctor closes for lunch at midday and still there are 40 people waiting, waiting since 9am and will continue waiting until the end of the working day at 5pm. Those that came from nearby would go home for the evening; those that came from afar would camp out at the clinic.

The clinic also holds workshops and special health testing. In Southern Africa, HIV is an enormous problem. Almost an entire generation has been wiped out from the disease. In Zambia it is estimated that a quarter of the population are infected. In Botswana the figure is as high as one in two persons. But it’s still a taboo in many parts, especially amongst men. They don’t want to know. The effort that was in process at the time we were there was to encourage pregnant women to get tested. If they are found to be positive and found early enough there are drugs that they can take to minimise the chance of it being passed on to their children. They are encouraged to come in as a couple and have both partners tested. There are a few couples there, all young, in their late teens or early twenties, that come in for the once a week drop in testing but not nearly enough as the health workers would like them to. “It’s mainly the men refusing to come.” Says one of the nurses, “They don’t want to know.” But the fact that there are some there shows that attitudes are changing and diagnosis is the first step in eradication.

In the final set of buildings there is a child development workshop happening. Delegates have travelled far to attend this three day workshop, learning how to prevent malnutrition in growing children. Some stay with friends and family that live close by, others sleep at the clinic, on the concrete floors under the stars. During the breaks there is a buzz of amiable chatter emerging from their side of the clinic. Sometimes they sing, a beautiful chorus of voices, smiling and laughing. For our help in the registration office, Mrs. Kabushca took it upon herself to have everyone thank us for our help. She ushered into the waiting room where we got an applause from the patients, to the consultation room to say goodbye to the doctor despite him being mid-consultation, to the conference building where the delegates were having a break. “Sing!” she commanded in a loud voice, in that stern voice that only Mrs. Kabashca can get away with. Mrs. Kabushca started them off, her voice though is far from sweet. They didn’t need much encouragement and laughingly they started to sing some Zambian folk songs. We joined in the singing and dancing, miming and then sounding the words as we got used to them. It was one of the happiest and most joyful experiences we had.

Such appreciation! But for what? We only helped out with some menial administration activities. We weren’t skilled health workers so we couldn’t do anything else, nor were we qualified to do so. But still, they appreciated the little help we gave them, to allow them to share their world with us and is the reception that all visitors get: Unbounded friendship and love.

But we are skilled; I’m an aeronautical engineer, a highly skilled profession and one that they don’t see very often in these parts. But they don’t have much use for such a high technical skill; there isn’t a burgeoning aircraft industry in this village, or even Zambia as a whole. But then I thought about the math lesson that we sat in on a couple of days ago at the local school. The pupils were learning basic mechanics but the applied examples that they had to solve were straight from a very boring textbook. Surely there was more interesting applications and examples to use and aircraft are, for most of us, fascinating. I proposed to Mr. Moses the headmaster to take one of their math classes and talk to them about aeronautics. He eagerly agreed, beaming with smiles.

The school had two classrooms, an office and a play area outside. It was a simple single storey brick construction with corrugated iron roof. Three steps leading out of the dirt playing field led through the front entrance into the lobby. Directly in front was the office of the headmaster and to the left and right the two classrooms. The classroom to the left was for the older pupils and the one to the right for the younger.

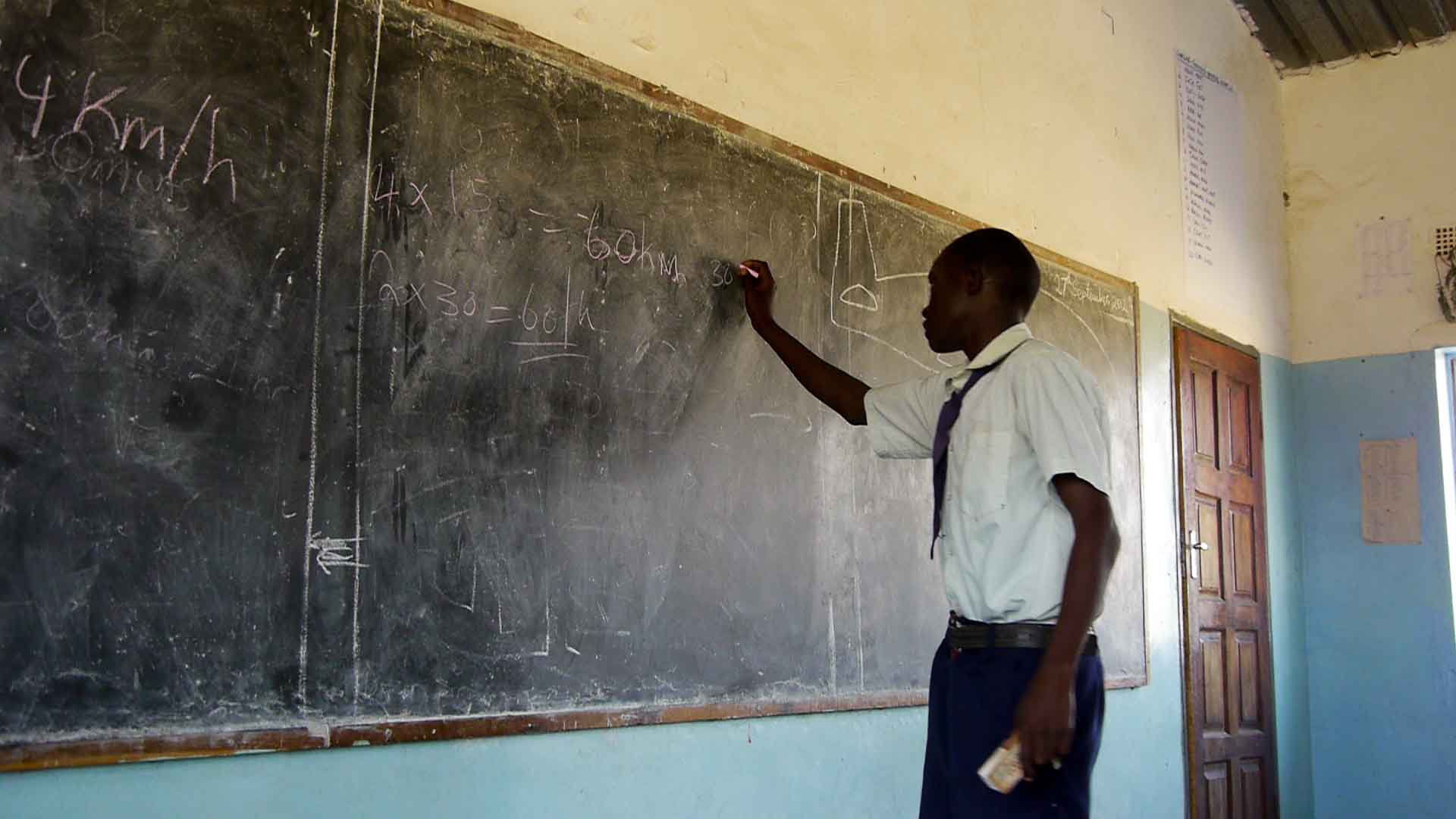

The interiors walls of the classroom was of the brick face of exterior walls, rough dark brown bricks with grey cement protruding and bulging out of the seams. The floor was of smooth grey concrete. A long blackboard covered the front of the room to the right of the door and in front sat fifty Grade 9 pupils on small wooden splintering desks. They wait patiently as I am presented. As with the impeccable politeness of all Zambians they stand when I enter the class room, greeting me formally yet warmly. I forgot to ask them to sit and they continued standing until Mr. Moses intervened and gave the instruction to sit.

As with schools in the UK, all the pupils wore a school uniform, shirt and tie for boys and skirt, blouse and jumper for the girls which seemed far too warm for this climate. At this age in school, their shirts were not torn or over used as was the case with all the younger classes and almost all had a note book to write in. My attire in shorts, short sleeved shirt and flip flops all extensively worn from months of travelling was, in comparison, a little embarrassing.

The most that any of these children had ever gotten to an aircraft is seeing the large airliners silently cruising through the blue skies kilometres above them, tiny specks slowly passing by leaving a trail of white. Had they ever asked themselves about how it could fly? Or even how big these aircraft were? I started at the beginning. They were astonished to find out that these specks were huge, transporting the size of their village half way across the world. The look of awe in their wide eyes as they comprehended these incredible feats of human ingenuity made everything else irrelevant. Their shyness, coupled with ignorance soon gave way to intrigue and fascination. They were understanding aircraft and helicopters and many of whom have never even been in a car before. They learnt about what the wings do, what the engines do, what the landing gear does.

They started answering the questions I posed them. One boy even answered correctly as to why the aircraft needed a tail using his knowledge of the large African birds that soar overhead. Another correctly answered as to what would happen if the aircraft started to go too slowly. Their questions too became more sophisticated, 'Sir, how do you get oxygen into the aircraft?', 'Why can't you open the windows?'

The greatest part of the lesson was taken up by practical maths. They were to work out in relation to other modes of transport how fast an aircraft travels. Speed is not something they are accustomed to. The question 'How fast can you travel by bike?' Was met with shrugs until they could think about how far their house was and how long it took to get to school. 30 minutes to travel 7km equals 14km/h. The car, which most had never travelled on, yet seen whizzing past on the road on the edge of the village was worked out to be at 120km/h. But how do you work out the speed of an airliner?

When they worked out the speed at 972km/h they were astonished! Shouts of surprise and murmurs of disbelief filled the classroom and exploded to a raucous when they found out that fighter jets, at an air force base close by, can travel at 2-3 times that speed.

Hands were shooting up now and the questions flowed one after another. But time was now over and I left them in a state of wonder.

As Mr. Moses, the senior teacher, said as we left, "Thank you. It is inspiring to the young village children to realise where they can emerge with studying and the usefulness of it."

So what if they never get the opportunity to become an aeronautical engineer. So what if at the end of it all it was just an entertaining afternoon for them. It was educational and it sparked a curiosity, where that curiosity will take them no one knows and for that I feel, justly, appreciated for.